After my blog post last week about MSG, one of the fantastic archivists here at Chemical Heritage Foundation unearthed this incredible artifact. "15 Delightful Recipes Prepared in a New Way," a cookbook and extended advertisement for Aji-No-Moto, a monosodium glutamate seasoning manufactured in Japan by S. Suzuki & Company.

There's no date on this, but — based on what I know about Aji-No-Moto, on comparable advertisements, and from the lady's outfit in the cover illustration — I'm fairly sure it's from the early 1930s. At that time, the consumer market for monosodium glutamate in Japan was booming; Suzuki wanted to find a similarly vaunted place for Aji-No-Moto in the U.S. home kitchen.

Aji-No-Moto was the most popular brand of MSG in Japan, but the product and the chemical would have been utterly unfamiliar to the vast majority of US shoppers. So, Suzuki not only had to introduce Americans to Aji-No-Moto, it also had to educate American consumers about how to use it. The advertising pamphlet-cookbook was a common tactic of food manufacturers -- you've probably seen some examples of these with recipes for Jell-O, Crisco, or Fleischmann's Yeast in used bookstores or antiques shops -- and this is a pretty typical example of the form, interlarding practical recipes with expository advertising copy and other inducements.

In addition to how to use Aji-No-Moto, consumers needed to know why. Every new product has to make its pitch, provide a narrative motive for buying by describing (or creating) the problem it's going to solve, the intervention and improvement that it will make in the one and only life of the consumer.

Specifically, this was the problem for which Aji-No-Moto proposed itself as a solution: "jaded appetites."

This was a problem that afflicted women in particular:

To women who daily face the trying problem of having something different for breakfast, luncheon and dinner, or how to make left-over dishes more appetizing, the Orient now sends one of its rarest secrets.

Modern, middle-class women, the scientific managers of the household, were tasked not only with preparing nutritious and wholesome meals on a budget, but also with providing an appetizing and stimulating variety of dishes. Without endless novelty, there would be thankless drudgery. Aji-No-Moto makes it new.

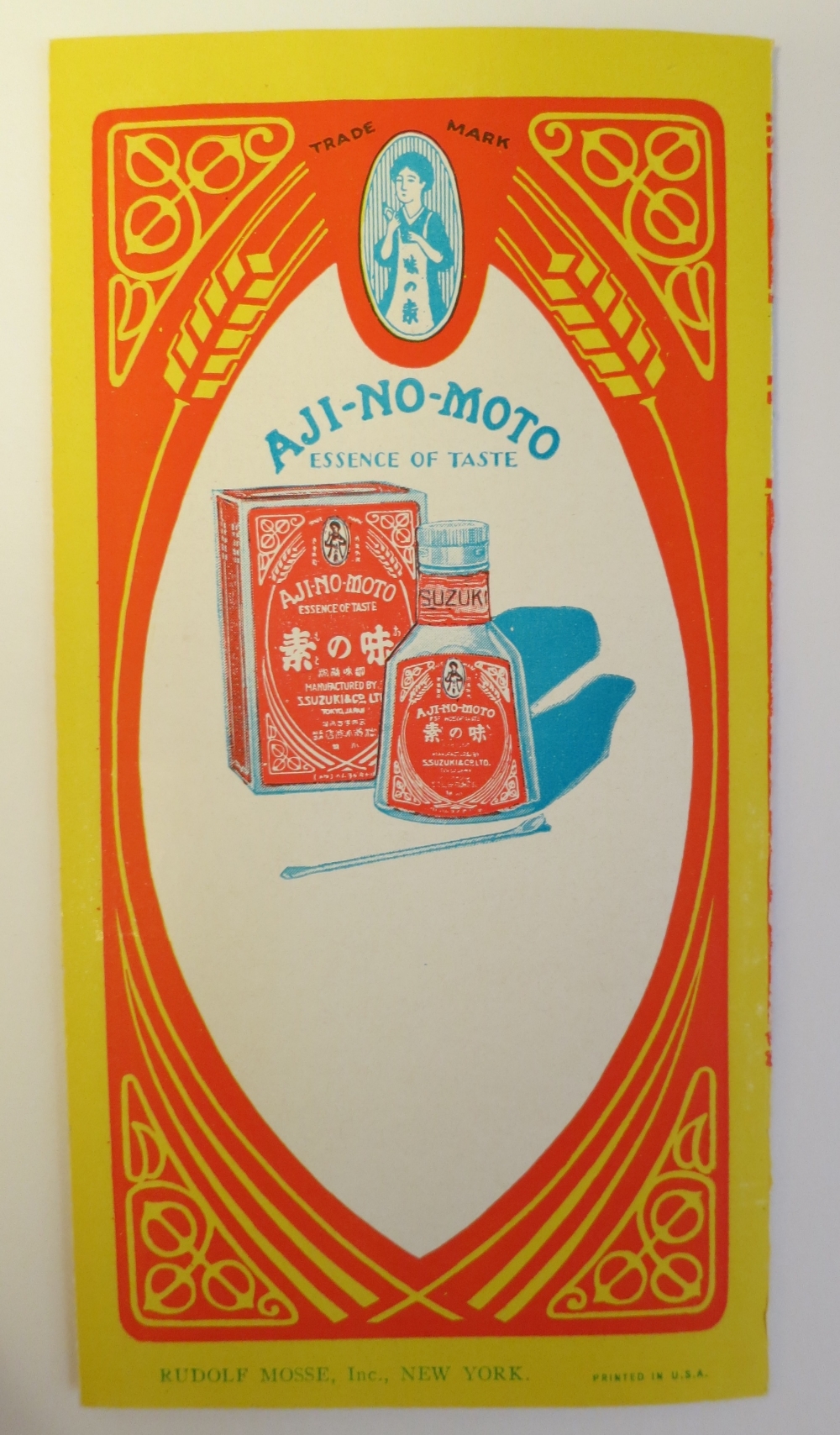

"Well, that sounds very fine indeed," the woman reader, circa 1930, might as well muse, wondering if this rare secret could help her turn the left-over roast beef congealing in her ice-box into something her fussy children and bratty spouse would not refuse to ingest. "But what exactly is Aji-No-Moto?" The pamphlet scrupulously evades this question. We are told that the name means "essence of taste," but there is no mention of monosodium glutamate, MSG, nor the raw material or industrial process by which it was manufactured. A closer look at the back cover reveals a pair of highly stylized wheat-stalks, cadmium yellow on red ground, enclosing within a mandorla a spare tableau of Aji-No-Moto box, glass bottle, and dainty spoon. This is crowned by an emblem, in cool blue, of an aproned Japanese woman. The twin ears of wheat refer obliquely to the wheat gluten origins of the seasoning; a Good Housekeeping (Bureau of Foods, Sanitation, and Health) Seal of Approval, as well as the assurance that "some of America's leading cookery experts... endorse" Aji-No-Moto "for its purity and wholesomeness" are meant to quell any possible misgivings about the product's safety.

Aji-No-Moto is defined not by what it is, in a material sense, but by what it does -- its effect on foods, on eaters, and on the status of the cook herself.

First, it is a general seasoning, with "practically limitless" applications in foods. The pamphlet contains instructions and recipes for its use in soup, rice and noodles, vegetables, sauces, salad dressings, meat, fish, and eggs. It is simple to use, a kin to the most familiar seasonings: "use it just before serving as you would salt and pepper, or at the table."

But the "super-seasoning" does more than salt and pepper ever can. Aji-No-Moto not only improves the food; it also improves the cook. Aji-No-Moto collapses the difference between domestic cooking and fine cuisine, bringing the gourmet chef's refined effects within reach of the housewife and elevating her home cooking above the realm of the quotidian. We are told that Aji-No-Moto is "a zestful persuasive seasoning that immediately gives the most commonplace, every-day dish that indefinable something that makes one cook's meal a welcome surprise and another's 'Just something to eat.'" It "gives to every dish that rich, full-bodied flavor that forms the basis of the famous sauces, soups and other culinary triumphs of the foremost professional chefs." Moreover, it produces these effects as if automatically, without adding any drudgery or time to the process of cooking -- for instance, it "eliminates the laborious process of boiling down beef-stock in order to obtain a meaty flavor." In short: it increases joy, without sacrificing efficiency.

What is this "indefinable something"? How does it work? The pamphlet offers the following account of Aji-no-Moto's operations:

[It] is the only seasoning which reveals the 'Hidden Flavor' of food. Untasted in every dish you eat is flavor that makes food more tempting -- delicious -- appetizing, but whose presence is often unsuspected. Aji-No-Moto reveals and enhances this natural flavor and adds a mellow zest all its own.

Aji-No-Moto thus apparently has a transformative effect on foods and on diners. It transforms foods not by adding an additional, unfamiliar flavor component, but by inducing foods to reveal their "unsuspected" depths. It transforms diners by reeducating their senses and recalibrating their appetites -- by making them susceptible to the flavor they had been consuming all along without suspecting it, the natural flavor that had passed down their gullet untasted.

The challenge of selling Aji-No-Moto to American consumers is in making the chemical comprehensible -- in balancing familiarity with novelty, but also balancing (scientific) modernity with enchantment and magic. This is why, I think, it Aji-No-Moto persists in being introduced as a "rare secret of the Orient," while also making every effort to appear westernized and domesticated, adaptable to a range of familiar Western dishes. Aji-No-Moto does not abjure its origins — converting itself into a deracinated chemical — but flaunts its Eastern mystique. And while the product's name may be transliterated into Latin script and its meaning translated into mystical English ("Aji-No-Moto means 'Essence of Taste'"), it retains Japanese lettering its packaging, a Japanese housewife on its emblem, and boasts of its endorsement by "The Imperial Household of Japan."

Aji-No-Moto did not take off with American housewives in the 1930s the way it had with their counterparts in East Asia. It appears that American home cooks came to think of it mainly as an Asian condiment rather than a general seasoning. Indeed, the only recipe from the 1930s using MSG that I've encountered so far comes from a 1933 Chicago Tribune column by food writer Mary Meade; she uses it in "sukiyaki," in a column about throwing a Japanese food party. Although Aji-No-Moto continued to be sold in the US throughout the 1930s and 1940s, it appears not to have been widely available. Its sale seems to have been restricted mainly to Asian groceries in large cities.

Despite its apparent lack of success in making a place for Aji-No-Moto in the American cupboard, this pamphlet is fascinating for the ways it prefigures future campaigns to sell monosodium glutamate to home cooks: its associations with professional cooking and plush gourmet qualities such as richness, savoriness, and fullness; its pitch to housewives seeking transcendence from the thankless drudgery of routine cooking; its promises of "inestimable delight," of untasted, unsuspected flavors, flavors that have been there the whole time.